THE BLAYDON AND STELLA KEELMEN

Whilst a large community of keelmen resided at Sandgate, Newcastle, there was a very significant amount of keelmen activity at Blaydon and Stella staiths. Also at Derwent Haugh staiths, at Dunston staiths and on the north bank at Newburn and Bell's Close.

In his history of Whickham Parish, Bourn states "for a long time (prior to the industrial revolution) the keelman were the largest class of the local working population. They were rough, hardy, exceedingly clannish and jealously guarded their supposed priviledges. In 1704 there were four hundred keels employed on the Tyne and about one thousand, six hundred keelmen. The work was extremely arduous and tiresome and they were exposed to all kinds of weather"

In the days before the industrial revolution Blaydon was no more than a few farm settlements and keelmen's cottages but also the keelmen had lodging places eg. the old Dockendale Hall in Blaydon Burn.

The community of keelmen had a considerable amount of cargoe to carry from these staiths, down river, to the sea going boats moored up at Newcastle and east down to the mouth of the Tyne. Cargoes of locally mined coal, fire bricks and lead (carried all the way from the Alston area and the north pennines, by trains of pack horses and later wains, down the lead road via Greenside to Stella/Blaydon staiths).

The opening of the railway through Blaydon, in the 1830s had a devastating effect on their jobs then later the dredging of the river in the 1870s more or less finished off the trade. Hereunder is some general information about the keelmen.

PREFACE

The industrial revolution and north east England were profoundly entwined. Mining, shipbuilding, chemical industries, foundries, engineering works - and much more. Of all these mining and the shipment of coal were perhaps the most significant and emotive. Much has been written about our mining tradition. Local coal was being commercially mined way back, for example Winlaton coal was shipped to London in the fourteenth century.

Ancilliary to it was the vital work of the legendary keelmen - an amazing community with its own customs, politics, work ethic - even a unique dress code, a uniform of a short blue jacket, slate-coloured trousers and yellow waistcoat, and a black silk, flat-brimmed hat.

The trade goes back hundreds of years and embodies keelmen, watermen and later wherrymen (wherries (or skiffs) being a larger type of keelboat therefore more efficient).

The trade was seasonal - in earlier times coal was not shipped during winter conditions. Many of the keelman were from the borders - North Tynedale, Redesdale and into Scotland.

The following information has been extracted mostly from Wikipedia. See acknowledgement at bottom of page.

The KEELMEN

The Keelmen of Tyne and Wear were a group of men who worked on the keels, large boats that carried the coal from the banks of both rivers to the waiting collier ships.

Because of the shallowness of both rivers, it was difficult for ships of any significant draught to move up river and load with coal from the place where the coal reached the riverside. Thus the need for shallow-draught keels to transport the coal to the waiting ships.

The keelmen formed a close-knit and colourful community on both rivers until their eventual demise late in the nineteenth century.

BEGINNINGS OF THE COAL TRADE

Coal began to be exported from the River Tyne from the mid-thirteenth century onwards. The first recorded shipment of coal from the River Wear was in 1396. The early pits from which coal was exported were near the riverside so that as little effort as possible was required to haul the coal to the banks of the river. The coal was carried to London and elsewhere in colliers; small wooden sailing ships that sailed down the east coast. At this time both the Tyne and the Wear were not easily navigable for ships of any significant draught. The mouth of the Tyne was obstructed by Herd Sands and Bellehues Rock, as well as by a bar that ran across the mouth of the river. Further up river there were various shallows on which a ship might ground. In addition, the stone bridge at Newcastle prevented colliers from reaching coal deposits further up the river. The Wear was similarly difficult for ships to access. Both rivers were very shallow near the banks, which made it very difficult for ships to approach for loading. As a result of these navigation problems it was necessary to load the coal into the shallow-draught keels and transport it downriver to where the colliers were waiting.

THE KEELS

The keels were wooden boats with a pointed stern, so that the bow and stern looked almost the same. They were of shallow draught so that when fully loaded they drew only four and a half feet. The keels were forty feet long and at least 19 feet wide amidships: a very broad configuration. In 1266 the standard load of a keel was set at 20 chaldrons (wagonloads) or approximately 17 tons. After 1497 the keel load was frequently increased, until in 1635 it was set at 21.1 tons. A chaldron was a horse-drawn wagon containing 17 cwt of coal. Keels were supposed to be measured by the Kings Commissioners and given a load mark to show when they were full. The keels had a single mast with a square sail attached to a yardarm and two large oars. They had no rudder and so a large sweep was used for steering when the keel was under sail. The oars were used to row when the wind was not favourable. There were also two iron-shod poles for polling the keel through any shallows. The floor of the hold was only two feet below the gunnel to allow for easy loading. The coal was piled high above the top of the hold with wooden boards used to prevent the cargo from sliding. Each keel was manned by a skipper, two crewmen and a boy, known as a ‘pee dee’. The meaning of this title is unknown.

THE KEELMEN'S WORK

The keelmen would start by loading coal into the hold from a 'spout', as the riverside chutes were called. The keel would then be taken down river on the ebb tide using the oars, or the sail, if the wind was favourable. The keel would then be taken alongside the waiting collier and the crewmen of the keel would carry out the strenuous work of shovelling the coal into the collier, working even after darkness. Because of the difference between the keel’s gunnel and the collier’s deck, this could be very arduous work. After a time colliers were constructed in such a manner as to make it easier to load coal into them. In 1819 the keelmen went on strike, and one of their demands was an extra shilling per keel for every foot that the side of the collier exceeded five feet. After completing the loading of the coal, the keelmen would return for another cargo, if there was time left in the day and if the tides allowed.

The keelmen were traditionally bound for employment for a year, with the binding day normally being Christmas Day. Their employment tended to be seasonal with hardly any work in winter. The availability of work was often affected by the weather, if ships were unable to come into the river, and also by the supply of coal from the pits. Strikes might affect output, and the wily pit owners would sometimes curtail production to keep prices high. As a result the keelmen could spend long periods without work, during which they would have to exist on credit. In slack times keelmen could sometimes find employment in clearing wrecks and sand banks from the river. The Tyneside keelmen formed an independent society in 1556, but were never incorporated, probably because the Newcastle Hostmen feared them becoming too powerful. The Wearside keelmen were finally incorporated in 1792, by Act of Parliament. The Tyneside keelmen lived in the Sandgate area outside the city walls, one of the poorest and most overcrowded parts of the city, made up of many narrow alleys. They were known to be a close-knit group of aggressive and hard-drinking men. John Wesley, after visiting Newcastle, described the inhabitants of Sandgate as being much given to drunkenness and swearing. The work of a keelman was physically very demanding and most men were unfit to continue the work into their forties. When dressed to go out, the keelmen would wear a costume that distinguished them from other workers. This was a blue jacket, a yellow waistcoat, bell-bottom trousers and a blue bonnet. The trade of keelmen tended to be passed on from father to son, the son working as an apprentice on a keel until considered old enough and strong enough to be a crewman. By 1700 there were 1,600 keelmen working on the Tyne in 400 keels. Not all of the keelmen were local. There was a significant number of seasonal Scottish keelmen who returned home to Scotland when trade was slack in the winter.

THE HOSTMEN

Disputes with the Hostmen - The Tyneside keelmen were employed by the Newcastle Hostmen and were often in dispute with their employers. They went on strike in 1709, 1710, 1740 and 1750. One grievance held by the keelmen was that the Hostmen, in order to avoid custom duties, would deliberately overload the keels. Duty was paid on each keel-load, so that it paid the owner to load as much coal as possible. This meant that the keel-load gradually increased from 16 tons in 1600 to 21.25 tons in 1695. As the keelmen were paid by the keel-load, they had to work considerably harder for the same pay. Even after the keel-load had been standardised, there were cases of keel owners illegally enlarging the holds to carry more coal, as much as 26.5 tons. In 1719 and 1744, the Tyneside keelmen went on strike in protest at this 'overmeasure'. The 1750 strike was also against 'overmeasure', as well as against 'can-money', the practice of paying part of the keelmen's wages in drink that had to be consumed at 'can-houses', pubs owned by the employers.

EXPANSION OF COAL TRADE

The coal export trade from the Wear was slow to develop, but by the seventeenth century there was a thriving trade in exporting coal from the Durham coalfield via the River Wear. The tonnage however was much smaller than on the Tyne; in 1609, 11,648 tons were exported from the Wear compared with 239,000 tons exported from the Tyne. This imbalance changed dramatically during the English Civil War because of the Parliamentarian blockade of the Tyne and their encouragement of the Wearside merchants to make up for the subsequent shortfall in coal for London. Coal exports from the Wear increased by an enormous amount, causing a similar increase in the number of keelmen employed on the river. By time of the Restoration in 1660, trade on the Tyne had recovered, but the river was now only exporting a third more coal than the Wear.

THE KEELMAN's HOSPITAL

In 1699 the keelmen of Newcastle decided to build the Keelmen’s Hospital, a charitable foundation for sick and aged keelmen and their families. The keelmen agreed to contribute one penny a tide from the wages of each keel’s crew and Newcastle Corporation made land available in Sandgate. The hospital was completed in 1701 at a cost of £2,000. It consisted of fifty chambers giving onto a cloister enclosing a grass court. One matter of contention relating to the hospital was that the funds for its maintenance were kept in the control of the Hostmen, lest they be used as a strike fund by the keelmen. The hospital building still remains in City Road, Newcastle, and was used for student accommodation until recently.

THE PRESS GANGS

Because of their experience of handling boats, the keelmen were considered useful in times of war when the Royal Navy required seamen for its warships. During the French wars of the late eighteenth century, the Naval Impress Service would have liked to impress as many keelmen as possible, but the keelmen were officially protected from impressment. However in 1803, during a time of crisis, the Tyne Regulating Officer captured 53 keelmen with the intention of impressing them into the navy despite their exemption. In retaliation, their wives took up whatever was handy (shovels, pans, rolling pins) and marched to North Shields intent on using any means to rescue their men, whilst the rest of the keelmen went on strike until the captured men were released. A compromise was reached so that 80 ‘volunteers’ (one in ten keelmen) would be accepted into the navy and the rest would be exempted from impressment. A levy was to be paid by the coal-owners and keelmen to provide a bounty for the keelmen who joined the navy. A similar situation existed on the Wear, except that the keelmen there were treated less generously. They had to provide a similar quota of recruits with two landsmen counting as one prime sailor.

COAL STAITHS

About 1750 a new development began to be used on the Tyne. New pits were being sunk further and further away from the river and coal was being brought to the riverbank via wagon ways.Once there, in places accessible by colliers, coal staithes were built to allow coal to be dropped directly into the holds of the colliers without the need for keels. The staiths were short piers that projected out over the river and allowed coal wagons to run on rails to the end. Colliers would moor alongside the end of the staiths and, initially, the coal from the wagons was emptied down chutes into the colliers’ holds. Later, to avoid breakage of the coal, the coal wagons were lowered onto the decks of the colliers and were unloaded there. This was the beginning of the end for the keelmen and they realised the threat that the coal staiths posed. Strikes and riots resulted whenever new staiths were opened. In 1794 the Tyneside keelmen went on strike against the use of staithes for loading coal. Because of the shallowness of the Tyne, the use of coal staiths did not entirely obviate the need for keels. The amount that the staiths projected into the river was limited so as not to obstruct river traffic, so that the staithes ended in shallow water. As colliers were loaded their draught would deepen until often they were no longer able to continue loading from the staithes. In such cases the colliers would have to move into deeper water and the loading would be completed using keels. Until 1800, the most productive pits were situated upriver from Newcastle, and colliers could not pass the bridge there to load coal. After 1800, coal production switched to further down river, where coal staiths could be used. Already, by 1799 the number of keels working on the Tyne was 320 compared with 500 at the peak of their use. At this time, the Wear, with a smaller output of coal, employed 520 keels. Coal staithes were not introduced on the Wear until 1812, but were resisted just as strongly by the keelmen there. They rioted in 1815 in protest at coal being loaded via coal staiths.

RAILWAYS

A rapid growth of the rail network occured from the 1830s onwards. Eventually used for transporting coal (as well as using coal), this had a hugely detrimental impact on the keel trade. In addition, some of the rail tracks, as they tended to follow flat river valley routes, actually severed the easy access of the wagonways to their river jetties.

STEAM TUGS

Another threat to the livelihood of the keelmen was the development of steam tugs. During a ten-week strike by the keelmen of both Tyne and Wear against the use of coal staiths, the keel owners installed one of the newly developed steam locomotives in a keel equipped with paddle wheels. The keel was not only able to propel itself, but was able to tow a string of other keels behind it. By 1830, Marshall’s shipyard in South Shields had begun to manufacture steam tugs, for the Tyne and for further afield. This development did not threaten the livelihood of the keelmen as completely as the development of the coal staiths.

RIVER DREDGING

As mentioned above, the reason for employing keelmen was the poor state of the navigation on the Tyne and Wear, which prevented ships from moving up river without danger of grounding. As time went by this situation gradually worsened. Colliers arriving at the river mouth would have a ballast of sand that had to be disposed of. The correct method of doing this was to deposit the sand on specified areas on the riverbank provided for the purpose or by depositing the sand in the sea. The Wear had ballast keels that were used to unload the ballast from colliers and take it out to sea. There were penalties for depositing ballast in the river, but this often occurred. The result was that the riverbed became silted up, causing even more navigational difficulties. Additionally, industry on the riverbanks often deposited its waste products in the river. The situation on the Tyne became so bad that in 1850 the Tyne Navigation Act was passed, which gave control of the river to the Tyne Improvement Commission. This body began an extensive program of dredging to substantially deepen the riverbed. This program was completed in 1888 so that the largest colliers could pass right up to Newcastle and beyond. This deepening of the river meant that colliers could load coal from the staithes without the need for keels to complete the work. In 1876 the existing bridge at Newcastle was replaced by the Swing Bridge, which rotated to allow ships to pass up and down river. This allowed colliers to be loaded from staithes above Newcastle and so further sealed the fate of the keelmen. The Wear Improvement Bill was passed in 1717, creating the River Wear Commission. Building was started on a south pier at the river mouth in 1723 and continued for many years. A north pier was completed in 1797. The piers were intended to improve the flow of water and prevent the river from silting up. The river was dredged in 1749 to improve access, but the use of keels continued undiminished until the introduction of coal staithes in 1813. In 1831 a new harbour was opened at Seaham, further down the Durham coast. This diverted much of the Durham coal away from Sunderland and further threatened the existence of the Wearside keelmen. In 1837 a North Dock was completed at the mouth of the Wear to load colliers and in 1850 a huge South Dock was completed with room for 250 vessels. These loading facilities obviated the need for keels except for inaccessible pits far up river. On the Tyne, three large docks were also constructed for loading coal: Northumberland Dock in 1857; Tyne Dock in 1859; Albert Edward Dock in 1884.

THE FINAL DEMISE

By the mid-nineteenth century, less than a fifth of the pits on the Tyne and Wear were using keels to load coal. The introduction of coal staiths and steam tugs had already severely diminished the number of keelmen. The rapid growth of the railways had a dire effect too. The new docks with their efficient coal loading facilities brought the final demise of the keels and the men who worked them. The second half of the nineteenth century was a time of rapid industrial growth on Tyneside and Wearside, so that the keelmen would be readily absorbed within other industries. They are now just a distant memory with little to remind us of them, apart from the Keelmen's Hospital that still stands in Newcastle and the well known local song, "The Keel Row".

The picture above is of a painting by Turner showing the keelmen on the Tyne and titled 'Keelmen heaving in coals by moonlight', 1835. It says it all really.

POSTSCRIPT

My ancestors on my father's side were keelmen and watermen. My great grandfather was John Danskin who was one of the last of the river keelmen (Bells Close, Newburn). He was my father's, mother's father - my father was James Danskin Veitch, his mother's maiden name Ellen Danskin. John's brothers were keelmen or miners. On my father's father's side of the family there are Blaydon watermen - Samuel Veitch and son William. The name Veitch probably originates in the Scottish borders (Dumfries region).

Matthew Veitch d1787 Occupation?

William Veitch b1786 - Occupation?

Samuel Veitch b1824 - d1901 of Newburn/Blaydon, waterman.

Samuel Veitch b1855 - d1914 of Blaydon, metal dresser (brother William a waterman).

William Veitch b1877 - d1945 of Blaydon, metal dresser.

Robert Danskin b1815 - d1881 of Newburn, river keelman.

John Danskin b1855 - 1940 of Newburn, river keelman later labourer at steelworks (brothers were keelmen/miners)

Ellen Veitch (wife of William) nee Danskin b1882 - d1969 of Newburn.

James Danskin Veitch b1919 - d1995 of Blaydon, metal dresser then NCB coke worker.

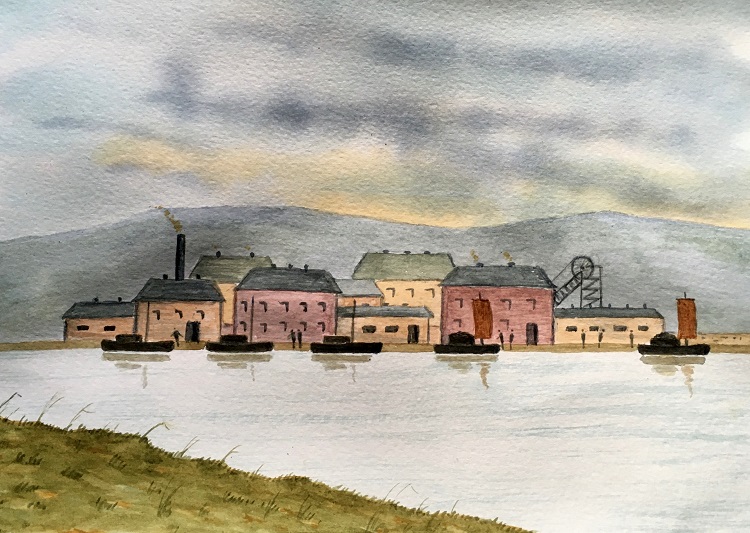

Pictures below - left, keelmans cottage, High Blaydon and right, its bricked up midden. Taken 5/3/2012. Then beneath some simple keelboat studies in watercolour.

Acknowledgement - with full credit to Wikipedia for much of the above information.

Roly Veitch

5th March 2012

Updated 18th January 2020

For more information on our local area history, our unique dialect, our wealth of dialect songs and other topics please visit the home page menu - link below.

Back to Home Page